- Home

- S R Savell

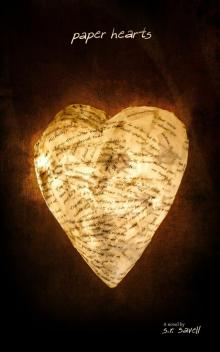

Paper Hearts

Paper Hearts Read online

To the man of steel with a heart of gold.

This is for you, Daddy.

Published 2014 by Medallion Press, Inc.

The MEDALLION PRESS LOGO

is a registered trademark of Medallion Press, Inc.

Copyright © 2014 by S.R. Savell

Cover design by James Tampa

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictionally. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

ISBN# 9781605426914

Chapter 1

Day 12 of Convenience Store Hell. Nineteen customers, two terrified civilians, no fatalities.

I jot this in my worn notebook, bound in stains and tears, cindered from too many stubbed-out cigarettes. Dusky light feels along its surface, spotlighting empty pages and an equally empty mind.

From the display case I take the yellow lighter, swiping it through the dying glow seeped into the countertop. Two green eyes disappear and reappear in the veneer of the metallic casing, irises warping as if in a Halloween house of mirrors. The room blossoms fire with the flick of a gear, the remaining thread of light evaporating into the dim.

Today I’m sure Father Time has fallen and can’t get up. Too lazy to clean and too restless to sit still, I spend most of my time wishing the hours away and failing to distract myself from the lagging minute hand on the clock.

On the far wall, where the roaches like to hide, rows of Monsters and Dasanis watch in cold fury from their glass cages. Overhead the fluorescent bulbs hum, casting shadows so deep that for a minute I expect demons to materialize and rip my throat out.

I give them all, roaches included, the middle finger and slump in the hard plastic chair numbing my butt.

It’s reversing, the time is. No way is the minute hand still locked on the nine.

I flip through my iPod, but not even music can soothe these nerves. This is what hell will feel like. I’m not particularly liking the paint. When was that history assignment due? I saw at my itchy nose until my back itches too. I drive a hand beneath the shirt just as the clanking cowbell announces a customer’s arrival.

The room inhales, squeezes out a groan. Even swelled to beast size, it can’t hold the presence in the door.

He glances around and ambles toward me, hands submerged in his pockets, prompting me unwillingly to my feet.

“Can I help you?”

He’s unshaven, though not completely unkempt. Shaggy hair, combed back, touches the collar of a ratty T-shirt. A monstrous hand rests on the counter, hiding all its scuff marks, the other fist still buried in his pocket. “Uh, maybe.” Black eyes make their second survey of the room, focus returning to my own. “Is anyone else here?”

“No, unless someone’s crawling around in the air vents.”

He nods. “When do you close?”

I glance at my cell. My coworker will arrive in fifteen minutes. “I’m leaving in five. Then it’s Danny’s shift.”

Too stupid for fear, my mother always said about me. I’m not particularly afraid, but I’m not too keen on becoming a statistic.

The hand returns to its pocket. A third look around the room. “Did Peter mention me?”

“Nope.”

He shuffles a bit, tanned skin wrinkling across his brow. “You sure?”

I nod, wishing for him to either shoot or buy something, whichever.

“Is he coming by here tonight?”

“Don’t think so.”

“Oh.”

Bangs fall into his eyelashes, and he runs them back into place with several sweeps. Some droop forward again, mimicking the set of his deep shoulders.

“Can I help you with anything else?”

“Well, uh, maybe.” He glances at the door.

“It’s almost closing time.”

“You said someone was coming to take over your shift?”

“I lied.”

He stares a second, startled.

I pick at my nails.

Finally a hand emerges from the pocket, quick, slides across the table, and withdraws, leaving its token.

I stare first at it, then at him.

His face is sheepish, apologetic, and for this reason I stifle the laughter bubbling in my chest.

It’s not a gun or even a knife but a little slip of paper: a check.

Then humor vanishes like ice in a flame when the stupidity of the situation soaks in.

It’s a check. And we don’t cash checks.

I’m all ready to tell the nimrod what physical impossibility he can go perform on himself when the blush he’s wearing makes me take another look at the paper.

The No Checks Cashed sign has no sympathy for the puny paper cowering on the counter, tipping a scale at precisely one dollar and eighty-three centavos. I’m in a good mood, or at least a reasonable one, so I dig out a buck and some odd change from my pocket and offer him the check and money.

He doesn’t move.

“You gonna take it or not?”

He reaches like I’m a piranha and he’s just hit the water bleeding.

I drop the paper.

Instead of retreating, the hand hovers. His face sags in uncertainty.

“You need me to tell Peter anything?”

The fist comes to a shaky close. “No, but, uh, thank you for—”

The cowbell clangs again.

“Michelle?”

An almond-eyed beauty with caramel skin and a disposition just as sugary all but sprints the distance between us, zebra-print purse slapping her hip. Nia Anderson, aka She Who Shits Sunshine, has just found the last place I thought safe from my secondary hell.

I don’t exactly dislike her. I don’t resent her or her life of excellence either. School cheerleader/student council leader/advanced placement student/volunteer worker—she’s all this and more, a willing slave to the idiocies of school life. Which is her thing, so more power to her, but Nia has a problem. She’s a fixer. Nia wants you to be like her, live like her, think like her, spewing inspirational quotes like Bible verses and inviting you to groups and clubs that never wanted you in the first place.

I give a halfhearted wave.

The guy’s still there, floor gazing.

She moves her purse to the arm farther from the man. “When did you start working here?”

“’Bout two weeks ago.” I wonder why she’s in this neighborhood. Charity, maybe. Typical.

“You like it?”

“A job’s a job.”

“So true. I started working at McDonald’s last week. It’s definitely been an adjustment.”

I grunt, blaring the music in my earbuds.

She waits and, when I don’t answer, smiles and heads toward the soft drinks.

The man lingers nearby, bangs drooping shadows across his cheeks.

“Have a nice night, sir.”

Our eyes meet before he scuttles away, a prisoner pardoned.

A deep exhale shrinks the room to normal, and we all can breathe again.

A headache’s coming on. A dull pressure sits in the back of my eyes, waiting to tear into my skull. I refuse to stop the music, though. The pain is never that bad.

“So, Michelle,” Nia says, sliding a V8 across the counter, “have you thought about joining student council?”

And the headache begins.

“Get your head outta your ass!” My scream is soundless against the blaring horn of the Mercedes, its smoldering taillight

s my farewell before it rips up the asphalt like an ax grinder to a rubber ducky.

Tucking the fallen earbud into its cradle and cursing my mother for loving her shit job more than her shit kid, I let my feet bring me to the bus stoop. A gray-haired dame with a nice gray shirt and glass eye to match, Deena lounges on her vinyl throne behind the leather steering wheel, her real eye watchful. I pay her no mind as I pay her fee, ignoring the disgusted snort that trails me down the aisle.

I hate the city. I hated it when I was three, and I hate now, especially with the eau de ass rising from the seat every time potholes meet poorly aired tires. I hate it all—every last puff of exhaust, each shrieking eggheaded brat. Most of all, I hate that I’m at its mercy.

The song’s end bleeds in the outside racket. A belch, a sneeze, and the rustle of a damp newspaper continue until I bring in the peace with the click of the Next button on my iPod.

Every day after school, I worked from four till eight at the Gas-N-Go, then waited for Mother Dearest to come get me because, apparently, it was too dangerous for me to walk two blocks to the bus station at night. Bullshit, I called it. A seventeen-year-old who can’t be trusted to get her own license because she’s unreliable and dishonest. That was how my mother put it. The school counselors, underpaid stooges without doctorate degrees, were never so honest. Couldn’t be. I’ve fished from their pot of hidden meanings that I’m in desperate need of a personality adjustment.

So I fed them gravy, I fed them wine, but never everything. I found it was too hard for them to digest. Or, rather, I was afraid that after searching through my Life Story of Unextraordinary Events, they would diagnose me as a nutso without a cause and put me in a padded room, no furnishings or windows included.

I was born, I grew up, and I came to this city, Cesspit 2, and started seeing a counselor once a week because it got me out of class. That’s all I said, period.

I said nada about my talent for hot-wiring anything with a motor, cats excluded. How I wouldn’t get to drive (legally) until I was eighteen because of my mother’s promise not to tell the cops of my midnight stroll with my grandma’s black Caddy at the bottom of the lake. About my parental units, Mother Karen and Father Michael, who conceived me in Cesspit 1, where Karen put herself through nursing school; meanwhile, Michael leeched off his rich mother to pursue his dreams of writing something readable, escaping from our creatively stifling apartment to more stimulating strip clubs, where he could write about Magnelius the Great and Ogarf the Friendly Ogre. I spared them the part about his equally magical disappearance and demise at the wheels of a runaway ice cream truck six years later. Thereafter, his mother passed, leaving Ma and me a settlement of one hundred thousand dollars and a house on the outskirts of—you guessed it—Cesspit 2. Here came the birthdays full of sticky cupcakes, brats muddying up the yard to play pig with the help of one strategically placed water hose, and nurses making me their personal pincushion. I especially didn’t mention when Womanhood sailed in, a pad and a handshake in tow. Giant pimples, strange shaving accidents, and insane mood swings started me on this road to pubescence. Stealing cars and kisses labeled me Demon and finished the journey, right around the time I left the Love Everybody highway and exited onto the Fuck Everybody roadway.

Pretty normal in the scheme of things. Sure, I had a few grains of stardust sitting in the dump that was my life, but besides those crumbs, my existence was the same as everyone else’s—lots of trash and very little treasure.

A while later I’m back in my butt-tranquilizing chair, waiting for Danny to leave.

He emerges from the bathroom, texting again. I’m convinced he’s symbiotically attached to his phone. He rubs his buzzed scalp. “Later.” He shuffles out the door.

This time as the cowbell tolls, the room betrays me. I’m re-retying my shoes when a dime rolls across the counter and chimes against the floor.

I sit up, dime in one hand and iPod in the other.

“Um, sorry.” It’s the guy again, wearing a timid smile and holding out a one and some odd change in one palm. “Here’s the rest of it.” His voice is deep like an idling diesel engine but quieter. Softer. I didn’t notice it when we first met, probably because I was preoccupied with the alarm button under the counter. His shoulders are hunched, and the longer I stare at him, the more they curl in like burning paper.

The little copper bits lie there, bright and dull, and I take them one at a time. His palm, carved deep with scars and lines, brushes against my fingertips. “Thanks.”

I bite one of the pennies, all coppery and new, then watch as his face breaks into a smile. The coin dangles from my mouth like a broken tooth, held there by the wet cushion of my lips. With a flick, the penny clinks onto the countertop.

“Can I help you?”

The smile on his lips stays there, unwavering, doesn’t fling away with the scoop of his hand through his hair.

It’s starting to unnerve me.

“I guess I do have a favor. Would you give this”—he pulls out a neatly folded paper from his pocket, a half-hidden word written in block letters on the front that look like Na—“to Peter? It’s important.”

I offer a nod, feeling the paper hot and small in the crook of my bent fingers.

“Um, thank you for, uh, everything. And I’m Nathaniel, by the way.”

I don’t offer my name until he asks.

“Michelle.” He almost tastes it as it passes his lips. “Well, um, I have to go. Nice meeting you. And thanks again.” With a brief wave and the clanging of the door, he’s gone.

My gnawed middle nail starts getting chewed again. I catch the corner of it, the most uneven part, and tug it clean across.

Too genuine to be genuine—that’s what he is/isn’t. The guy doesn’t seem natural, doesn’t seem to be what he should be, whatever that is.

Who bothers to return two bucks to somebody, anyways?

Heated needles stab at my knuckles. Bubbling against my skin, the paper demands attention. I can almost smell the ink, the sweated-on paper, the hidden words. It’s too much, too tempting, so I drop it, eying the smudged N in Nathaniel, wondering what kind of person over the age of eight even writes his name on the front of a letter. For a second I resist before hastily undoing the folds.

Dear Mr. Rodes,

I was hoping you would let me interview for a job next week. I would really appreciate it. If you can’t, that’s okay. You can reach me

My hands rip steadily until there’s a confetti shower over the wastebasket.

Good luck, asshole.

“Two friggin’ hours, and you don’t even bother texting me.” I slam the car door as hard as I can, satisfied when Mother flinches. She’s worn out, a bald tire going flat, but I shrug this awareness off in favor of a glare.

The ’99 Chevy Cavalier eases into traffic, leaving the empty Gas-N-Go behind.

“Look, I’ve had a long day. I’m tired and—”

“Late.” I drag it out, watch my egg donor heave out a long sigh.

She tucks a wisp of wavy cedar-red hair behind her right ear and flings me a look.

“I was late because I had to fill in for a nurse who quit on the spot. Now my boss is telling me it’s permanent.”

“Tell her to stick it.”

The night lights dance through the windshield, patterns whirling across her messy scrubs. She shakes her head, a golden flash illuminating her cheek before flitting away. “No, I am not telling my boss to stick it. A job’s a job, and I like where I work.”

“But there are other hospitals. And we still have some of the money Grandma gave us.”

“Between my college loans, moving, taxes and back taxes, and your college fund, it’s pretty much gone.”

“So you don’t want to quit working there, and we’re near broke.” I shrug. “Then I guess you’re shit out of luck.” I put the other earbud in.

It gets yanked out. Hard.

I lash back, knuckles grazing her arm.

“Watch it, little

girl.” She’s got the look again, all bossy and angry.

I start to clap, the midnight glow bouncing off my hands.

She doesn’t speak, not until we’re home. My feet have stomped halfway up the carpeted stairs when she calls up, “You’re quitting your job. I can’t pick you up anymore, not with this new schedule.”

I turn, feel the earbud fall from my ear. “I like my job.”

“Well, I guess you’re shit out of luck, then.”

I give her my own look, nails in my palms. I take a few downward steps. “I’ll talk to Peter tomorrow. Maybe he can use me for a few extra hours in the evening.”

“No, honey.” The television clicks on, and I see her drifting, pale blue eyes disappearing behind her eyelids.

I go plant myself in front of her, teeth hurting from being mashed together. “Can I just talk to him?”

“You are not staying out that late on a school night.”

“I’ll be working, for God’s sake! Besides, I need the money and he needs the business.”

Her hands are twined neatly on her stomach, eyelids sealed so tight I’m sure sleep has won. Letterman babbles behind me about some celebrity mishap before it cuts to a commercial.

“Mom?”

“All right, all right, now go to bed.”

Chapter 2

I’m in an alley that stinks of piss and mildew and rotten food. Totally disgusting. But I like it. The damp concrete against my heels, the shroud of pollution poised overhead—it’s all so peaceful. It makes me want to smile. And once I start smiling, I can’t stop. I feel my mouth stretching wider and wider, so wide that my lower jaw rips from its hinges, but I don’t mind. Really, I don’t. It feels so nice to be happy, to smile, so I sit up and stretch the bottom jaw with both hands until it perches on my knees, loose flesh all that’s keeping my mouth together. And then I get a peculiar notion and I think, Where’s the floor?

Paper Hearts

Paper Hearts